Every moment in today’s reading from Paul’s letter to the Philippians is beautiful. These are words that anyone would want to receive from anyone. Words like:

“I thank my God for every remembrance of you, always in every one of my prayers for all of you, praying with joy for your partnership in the gospel from the first day until now.”

And

“It is right for me to think this way about all of you, because I hold you in my heart, for all of you are my partners in God's grace.”

And, finally,

“And this is my prayer, that your love may overflow more and more with knowledge and full insight.”

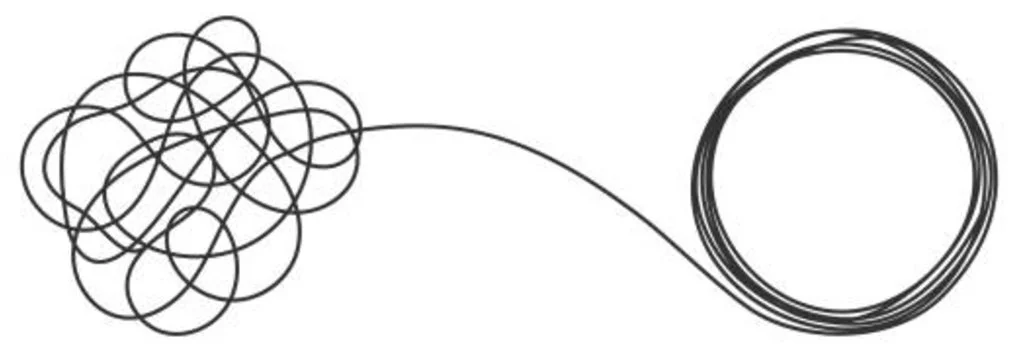

It sounds like Paul was having a good day when he wrote this. Such affectionate, tender parenting to this gathering of Christians in Philippi. But, in reality, Paul was imprisoned when he wrote this letter. Other parts of Paul’s letter describe his suffering in prison. Andy Rau, from Bible Gateway, explains that Paul “writes to the Philippians to show them that his imprisonment had not impeded the spread of the gospel, but had actually hastened its expansion. Paul draws attention to the significance of suffering in the growth of God’s kingdom, and offers the Philippians that same joy-in-spite-of-suffering if they will embrace that gospel message.”

Joy-in-spite-of-suffering: Henri Nouwen, who I quoted a couple weeks ago, from his book Finding My Way Home describes “The Path of Peace” through a man named Adam, with whom he lived, along with 8 other men in a community named Daybreak, where people with a mental handicap and their assistants try to live together in the spirit of the Beatitudes.

I’m going to quote from this book for the rest of the sermon, but don’t worry: I wrote out everything I wanted to quote and won’t spend time searching the book.

Adam “is 25 years old, and he cannot speak, cannot dress or undress himself, cannot walk alone or eat without much help. He does not cry or laugh and only occasionally makes eye contact. His back isn’t very straight and sometimes his movements seem distorted. He suffers from severe epilepsy and, notwithstanding heavy medication, there are few days without “grand mal” seizures. Sometimes, as he grows suddenly rigid, he utters a painful groan, and on a few occasions I have seen a big tear coming down his cheek. It takes me about an hour and a half to waken Adam, give him his medication, walk him into his bath, undress him, wash him, shave him, brush his teeth, dress him, walk him to the kitchen, give him his breakfast, put him in his wheelchair, and bring him to his Day Program.”

This sounds like a lot, right? Day in and day out spending your life with this man, helping him to live his life. But Nouwen discovers, as he spends more and more time with Adam that a kind of peace comes over him in this work.

“Adam’s peace is first of all a peace rooted in his being. Adam can do nothing. He is completely dependent on others every moment of his life. His gift is his pure being with us. Every evening when I run home to “do” Adam’s routine, to help him with his supper and put him to bed, I realize that the best thing I can do for Adam is to simply “be” with him. … I am simply here, present with my friend. How simple the truth that Adam teaches me, but how hard to live! Being is more important than doing.”

Henri Nouwen looks back at his life before joining Daybreak, up to and including his tenure at Harvard University. He left on a sabbatical from Harvard to explore the Daybreak community experience, and literally spent the rest of his life there.

Nouwen says, “As I sit beside the slow and heavily breathing Adam, I start seeing how violent my journey has been. This upward passage has been so filled with desires to be better than others, so marked by rivalry and competition, so pervaded with compulsions and obsessions, and so spotted with moments of suspicion, jealousy, resentment, and revenge. What I believed I was doing was called ‘ministry.’”

Henri Nouwen ends each day with Adam in prayer, not really sure that Adam understands what’s happening. So, Nouwen simplifies the moment and sits in his presence. “Since I began to pray with Adam I have also come to know better what prayer is about. Prayer is being with Jesus and simply spending time with him. Adam is teaching me that.”

As he moves through his life with Adam, Henri Nouwen experiences the simplicity of the work of Adam and the effect he has on the house. How simply his presence inspires peace in the community. Perhaps like long periods of time that Paul spent in the solitude of prison. “Adam is the weakest of us all, but without any doubt the strongest bond between us all. Because of Adam there is always someone home; because of Adam there is a quiet rhythm in the house; because of Adam there are moments of silence and quiet; because of Adam there are always words of affection, gentleness, and tenderness; because of Adam there is a patience and endurance; because of Adam there are smiles and tears visible to all; because of Adam there is always space for mutual forgiveness and healing… yes, because of Adam there is peace among us.

“Let me conclude with an old Hasidic tale that summarizes much of what I have tried to say,” Henri Nouwen writes as he concludes this chapter. And this sermon!

The rabbi asked his students: “How can we determine the hour of dawn, when the night ends and the day begins?” One of the rabbi’s students suggested: “When from a distance you can distinguish between a dog and a sheep?”

“No,” was the answer of the rabbi.

“Is it when one can distinguish between a fig tree and a grapevine?” asked a second student.

“No,” the rabbi said.

“Please tell us the answer, then,” said the students.

“It is, then,” said the wise teacher, “when you can look into the face of another human being and you have enough light in you to recognize your brother or your sister. Until then it is night, and darkness is still with us.”

“Let us pray for the light. It is the peace the world cannot give.”

And may that light “shine upon those who sit in darkness and in the shadow of death, to guide our feet into the way of peace." Amen.